By YULIA STESHENKO

Deconstructing Freedom

At the Live Your Life Summit, Misty asked us to not just have goals to strive for, but a vision for our future. Goals are finite and discrete. A vision can carry us through the uncertainty of our health conditions, beyond specific milestones, and offer meaning in the midst of struggles and setbacks.

I did not have a vision going into the Summit, but the word that came to mind as she spoke was “freedom.” (I thought this with a devilish glint in my eyes, as if it were a prison break I planned.) I didn’t know what I meant by this, but I’d have time to reflect and figure it out.

So here I am, two months after Summit, trying to understand what freedom looks like to me.

At first, I thought freedom meant walking as I did before MS. As I wrote in a MOC post about what I would do if I were not afraid of failure, what came to mind was being able to walk without fear of running out of energy or fear of needing a restroom I could not reach in time.

But afterward, it struck me that I can live quite well even with a rollator or even if it is obvious that there is something not quite right about my body. I am still free without looking as if I have been untouched by twenty-four years of MS. I do not have to be able to hide my MS to be free.

And freedom for me does not mean never using a wheelchair. I can live with this, too. I feel quite free, in fact, racing down hilly sidewalks, making my aide chase after me. Or even struggling up a curb cut and letting myself be assisted by a parent passing by with a stroller or a waiter who sees me in need. I do not mind accepting help when I have decided I want it.

I remember, one New Year’s Eve a decade ago, another guest, unaware of my disability, said emphatically she would not want to live if she needed a wheelchair. I thought, “You’d be surprised. There’s more to life than freedom from a wheelchair.” I wasn’t about to point this out to her, however, that life goes on and we find meaning nonetheless.

At another point, I thought freedom is being able to go out on my own, without someone to accompany me and ensure I am safe. But then I thought of my partner, who lets me decide where I wish to go and stands back as I propel myself, only stepping in when I am about to fly into a car or off a curb. I can live with this without feeling I am babysat. (Besides, I am not eager to have any more dental surgery.)

So none of these markers of freedom mean as much to me as I initially thought. Then what does freedom mean to me?

When I started volunteering for the local Center for Independence of the Disabled, offering financial planning support to others with disabilities, I couldn’t help wondering if I were a fraud. How could I offer advice to others when I relied on assistance of my own to get by—whether from my family, my partner or the federal and local government, which provided me disability income and health insurance, among other benefits? Wasn’t my independence a sham? I looked up the agency’s own interpretation and was relieved to see it conceived of independence not as complete self-sufficiency, or freedom from needing assistance or accommodations, but as the freedom to direct one’s own life and live on one’s own terms as much as possible. (I cannot find the specific quote, so I am paraphrasing here.)

OK, I met those standards of independence. I was not, in fact, an imposter. Phew.

Then, I thought of the other ways I had found freedom from beliefs and states of mind that had held me back.

Freedom from the guilt I carried for over a decade that I did not manage life after college as well as I “ought” to have, considering the tools I had available to me, including my education and support from my family.

Freedom from the shame that I was not the person others took for granted I could be.

Freedom from the fear I was a burden or inconvenience to others.

Freedom from a learned helplessness that kept me more cloistered and dependent than was demanded by my physical abilities.

Freedom from the isolation of not having others to connect with in meaningful ways.

It didn’t occur to me at the Summit, as I imagined a way of life just out of reach, but I already had this freedom, thanks to the MS Gym.

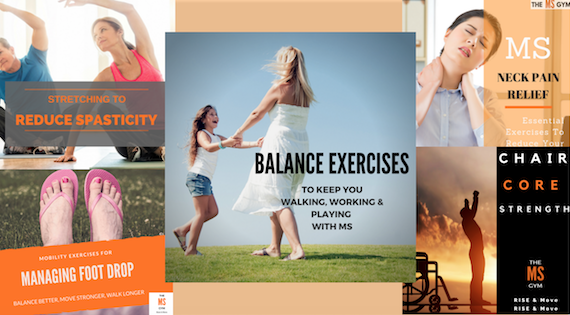

It enabled me to go off antidepressants after joining the MOC (yes, with careful tapering and the go-ahead from my therapist). And it enables me to strive for more visible, physical freedoms –to undo the asymmetry in my gait and walk for longer distances and strengthen my pelvic floor, and on and on.

I still strive to walk that mile that I don’t need to walk in order to be a fully deserving and contributing member of society. But I pursue it, knowing that it is a bonus to all the ways I’ve been freed already.

What does freedom look like to you? What freedoms do you have, as you are?